Several years ago at the very start of my journey into exploring democratic organizations, I visited Nixon McInnes, a digital consultancy company based in Brighton. They were in the process of experimenting with alternative forms of organizing as they transformed their company in a variety of interesting ways. It was an inspiring new organizational setting I experienced which influenced me and my subsequent work in a significant way. Most importantly, the interviews I conducted with members of the organization acted as the basis for a pilot study for an ESRC grant to study democratic organizations more broadly which led to, amongst other things, this website celebrating the ongoing success of the project and its findings.

One of the most interesting and unique cultural features of the company at the time was an approach which Nixon McInnes had labelled “the church of fail”. This light hearted initiative, which has subsequently gained a reasonable amount of press interest, was a monthly ritual in which staff members would come together to share organizational failures they had been directly involved with over the past few weeks. These might range from simple errors such as ordering the wrong office supplies to arguing with a colleague or more serious failures such as a loss of a client. The sessions would begin with an organizational member standing at the front of the gathering of workers as an “officiant” declaring: “Dearly beloved, we are gathered here today to confess and celebrate the failures of ourselves and our colleagues.” Individuals would then take it in turns to reveal their failures and rather than be met with looks of disdain and disappointment be greeted with rapturous applause. The idea, of course, was to make failure an acceptable thing to talk about and, indeed, celebrate talking about failure as a way of moving through it and past it so that we feel free to communicate and learn.

With this in mind, this blog post concentrates on failure. As academics we are routinely encouraged to celebrate our successes, and rightly so. We typically spend years in the process of developing journal articles, books, grants, teaching modules amongst other things, that when accepted deserve to be circulated in newsletters, tweeted about, shared on blog posts and talked about loudly in the pub over several large glasses of pinot grigio. Life in academia without celebration of each other’s success would be hollow. And yet, a much larger proportion of our time in academia is taken up by dealing with setbacks, knockbacks, rejections, or much more harshly framed, failures. For instance, whilst top journals in our field such as Human Relations now receive over 1000 article submissions a year, their acceptance rate is 6-7%. This means that 93% of us, in our submissions, fail in our efforts to publish at this esteemed outlet (I currently stand at 7 for 7 in rejections from this journal with articles on a variety of subjects – we submitted attempt 8 last month and are yet to hear back). Grant applications contain a similarly high level of expected failure with RCUK grant success rate hovering at around 15% depending on the scheme (last year a standard ESRC grant I submitted was rejected with very good reviews, but falling short of the outstanding ones required). Understandably, we tend not to advertise our failures though. Instead, we are encouraged (and become more accustomed over time) to mourn in silence, screaming into a pillow, dusting ourselves down and trying another more appropriate journal, funding body etc. Indeed, “finding the right home” for a piece of work – as if it is some kind of neglected dog in a shelter – is the current common parlance and comforting words that our (more supportive) colleagues might say to us.

But what happens when a piece of work doesn’t find a home? What happens if we continue to fail when submitting an article slowly working our way around prospective homes, changing the work, tweaking it to a point where we feel uncomfortable and frankly quite tired of doing so any longer? Where do journal articles go to die when they fail? I decided to use this blog post to bring one such “failed” paper out of the graveyard of my Dropbox so that it might live again as a reflection of one of my own personal failures. Perhaps using my ESRC funded website to post a 12000-word article I co-authored might not be deemed the biggest example of a failure, a sort of humblebrag if you will. However, failing to secure a home for this article was (and remains) genuinely frustrating, feeling that all those hours of research and writing with my co-authors had resulted in nothing. Other astute readers might argue then that this post is more of an attempt to reformulate a failure into a win, to grab (a small) victory from the jaws of defeat. But drawing on the lessons of my friends from Nixon McInnes, perhaps instead this is my own attempt to encourage an academic “church of fail” in which I encourage fellow academics to more regularly confront and talk about these painful failures, thus robbing them of their lingering power over us. I shall let you decide.

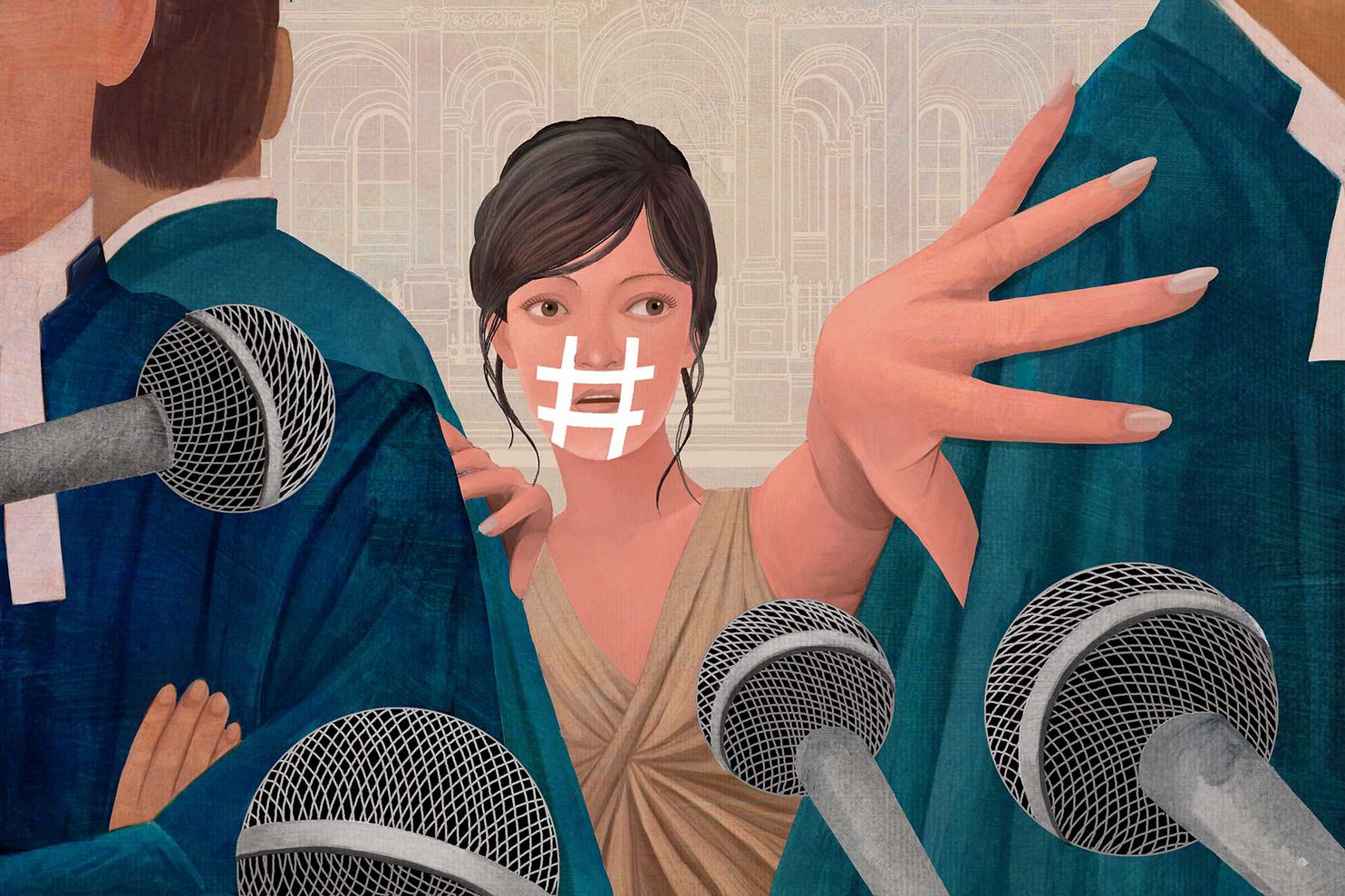

The “failed” article itself focuses on a significantly worse and darker failure brought to light by the recent #metoo movement to reveal widespread sexual misconduct and violence. It involves a failure of society for many years to listen and take seriously (predominantly) women’s stories about bosses’ harassment and sexual exploitation in the workplace and other spaces. It was with a shared interest in these kinds of organizational failures that my colleagues Prof. Mark Learmonth (Nottingham Trent University) and Prof. Gretchen Larsen (Durham University) and I decided to write an essay focussing, in particular, on the Weinstein sexual harassment case, in which dozens of women were preyed upon by the Hollywood director over the decades. Our work was inspired by two books that had covered the detail of the case at length showcasing both investigative skill and an eloquence to tell these women’s stories in an incisive, detailed but respectful manner. These two books, both published in 2019, were Ronan Farrow’s Catch and Kill: Lies, Spies and Conspiracy to Protect Predators, and Jodi Kanter and Megan Twohey’s book She Said: Breaking the Sexual Harrassment Story that Ignited a Movement, which has recently been turned in to a well-reviewed movie of the same name. Our essay departs from these accounts and attempts to draw out the management and organizational aspects and implications of their brilliant work to provide lessons for management studies.

So, here is my very first contribution to the academic “church of fail”. A rejected piece of work that simply could not find a home. The main issue with the work is that seems to fall somewhere between a book review and an essay without ever deciding entirely which direction to take. There are other issues no doubt that people will notice. Despite that, however, I think it offers some interesting thoughts about (and insights into) the Weinstein case and begins to consider the different ways in which organizational and management systems allowed (and still allow) vulnerable individuals to be abused in the workplace.

“HE’S FAR TOO IMPORTANT TO WEAR TROUSERS”:

MANAGEMENT THEORY IN THE WAKE OF THE WEINSTEIN SCANDAL

In October 2018, the New York Times published a list of 201 powerful men, and three women, who lost jobs, awards, contracts or reputations in the United States because of the #MeToo movement1 (Carlsen et al, 2018). Many of the perpetrators had been senior business people, and most faced multiple accusations. By the end of 2019, this figure had reportedly risen to over 400 in the US alone (Bloomberg, 2019). It seems that women2 are now starting to out senior colleagues as sexual abusers, and are being believed – with a frequency that was almost unimaginable until recently (Enright, 2019).

Even though certain forms of sexual violence are criminal offences, it is becoming clear that many women subjected to sexual violence by their bosses in the workplace kept quiet about it nevertheless. Although the reasons for their silence are complex, some of the factors are now beginning to come into focus. For instance, those who publicly accused their managers often faced blame or disbelief (Bergman, 2020), even from friends and family; not just from their HR Department. Furthermore, if anyone did leave his or her job because of an accusation against a boss, it was more likely to be the accuser than the perpetrator. Another important factor contributing to the silence has been the widespread use of non-disclosure agreements (NDAs). Many who left corporations after making an accusation of sexual violence against their manager did so with legally binding NDAs – designed to intimidate the accuser, and otherwise keep her mouth firmly shut. Although things do seem to have begun to improve, it remains far from clear whether all women who need to can now speak out freely about sexual violence by their bosses. As discussed later, given the complexities inherent in the formal and informal power asymmetries that typically play out in relations between senior male executives and their female subordinates (Pringle, 1988) – especially for younger, more junior women – it seems likely that significant numbers of women across the globe will continue to remain silent (and silenced) about sexual violence by bosses.

Much of the current debate centers on the activities of Harvey Weinstein, who received a 23-year prison sentence in February 2020 for a series of sexual assaults (including rape) he committed at work. Weinstein is, of course, a multi-award-winning film producer, so it is hardly surprising that the media generally portray him as a Hollywood movie mogul. We should not forget however, that he co-owned and ran two major companies (first Miramax and later The Weinstein Company). In many ways therefore, Weinstein’s work role was little different from that of any senior executive. While some of the survivors/victims of Weinstein were world-famous film stars (had they not been the subsequent media storm would doubtless have been much less intense), many others were ordinary company employees. For example, it was a junior former member of staff at Miramax, Laura Madden, who was one of the first employees to agree to go on record with allegations against Weinstein (Kantor and Twohey, 2019). Because Weinstein was, in many ways, just another executive, the ramifications of the case go well beyond the film industry, with major implications for all involved in organizations.

The implications for management scholarship are no less considerable than for many others with stakes in the matter. Indeed, we believe that #MeToo in general, and the Weinstein affair in particular have exposed major weaknesses in what we, as management scholars, know (and perhaps more importantly do not know) about the issues they raise. In this regard, it is surely telling that in the five years between 2015 and 2019 – across all of the Academy of Management’s journals – it is hard to find sustained analyses of sexual violence or even of sexuality more generally, beyond passing references. Nkomo et al (2019:505) comment that “sexual harassment, and sexual assault are some of the tools of terror nondominant group members face at work sometimes even in organizations purported to be diversity friendly”. Berti & Simpson (2019:34) believe that the #MeToo movement illustrates how sexual appeal, which is often considered an “asset” of female employees in particular, “became a source of exploitation”. Dewan & Jensen (2019) also touch on #MeToo as one of the scandals facing corporate America, and Stouten et al (2018:330) briefly reflect on #MeToo and its implications for voice and silence. The problem is that none of these papers develops fuller analyses of issues related to sexual violence. The only two articles to focus on the issues in a more sustained manner (Whiteman & Cooper 2016; de la Chaux et al, 2018) both center on the Global South. This focus is not a problem for the papers themselves of course, which both strike us as excellent research. However, because there are so few other analyses in Academy journals, the Global South contexts might be read to suggest that leading management scholars consider sexual violence at work to be of relatively minor significance, except in the Global South.

We should make it clear, however, that we believe our discipline can potentially contribute many valuable insights relevant to the debate nevertheless. There is, of course, a body of work on sexuality and organizational analysis (e.g. Brewis et al, 2014; Burrell, 1984; Hearn & Parkin, 1995) as well as on sexual harassment (e.g. Berdahl 2007; Bergman et al 2002; Bowes-Sperry & O’Leary-Kelly 2005; Chamberlain et al 2008; Dobbin and Kalev, 2020; Fernando & Prasad 2019; Lawrence, 2020; O’Leary-Kelly & Bowes-Sperry, 2001; O’Leary-Kelly et al, 2000; 2004; 2009; Peirce et al, 1998; Santos, 2020). We also believe that research on the “dark side” of corporate life, where “people hurt other people, injustices are perpetuated and magnified, and the pursuits of wealth, power or revenge lead people to behaviors that others can only see as unethical, illegal, despicable, or reprehensible” (Griffin & O’ Leary-Kelly, 2004:xv) may also be valuable. Work in this sort of tradition includes, among other examples, analyses of whistleblowing (Kenny, 2019), silence and voice (Morrison & Milliken 2000; Stouten et al, 2019), abusive supervision (Tepper, 2000), as well as executive narcissism (Braun et al, 2018) and executive wrongdoing (Fredrickson et al, 1988; Gabbioneta et al, 2019; Kundro & Nurmohamed, 2020; Martin et al, 2013; Palmer, 2012).

It remains our view however, that taken as a whole, organization and management research has largely been blindsided by the ramifications of the Weinstein case. As a community of scholars, we remain relatively poorly prepared to engage fully with the likely widespread prevalence and extremely challenging nature of many of the organizational problems that the Weinstein case (and the others like it) have unearthed. In particular, there appears to be a relative lack of well developed and up-to-date conceptual thinking on sexuality and specifically on sexual violence by senior executives in organizational life. To be clear, we are not claiming that management scholarship has been taken entirely by surprise about the existence of sexual violence by very senior people in organizational life. Our claim is rather that as a community of scholars we have not focused enough on the issue – so we have failed to emphasize the full significance (indeed horror) of its hugely negative effects for many people in organizational life; failed too, to see the extent of its prevalence and the insidiousness of how it can be practised and then covered up, especially by executives; and thus, most critically, we have failed to avert it.

These are the sorts of limitations that underlie our observation that it is hard to see how anyone could have derived from management research the sorts of insights recently expressed so forcefully by the Booker prize-winning novelist Anne Enright (2019:53). For her, the 201 powerful men on the original New York Times list mentioned above: “Especially at work … sexualised their dominance. They used sex to spoil women’s ambition and soil their talent. You might even say they were using sex to get ahead … And if they were powerful, no one stopped them.” Unfortunately, Enright’s no one includes us, as scholars.

In order to move thinking forward in this area, we therefore saw benefit in looking outside the confines of management scholarship, turning instead to two books by the journalists most heavily involved in exposing Weinstein. One is Ronan Farrow’s book Catch and kill: Lies, spies and a conspiracy to protect predators (Farrow, 2019); the other, Jodi Kantor & Megan Twohey’s She said: Breaking the sexual harassment story that helped ignite a movement (Kantor and Twohey, 2019). These books tell the stories behind the Pulitzer Prize Winning (2018) investigative journalism of Farrow in The New Yorker and of Kantor and Twohey in The New York Times, that when published in 2017 did (very directly) put a stop to Weinstein’s sexual violence. Their work has also indirectly stopped many others, in that their revelations about Weinstein ignited a powerful new wave of the #MeToo movement that by the end of 2019 had led (as mentioned above) to the dismissals of around 400 senior people in the US.

Both books became overnight bestsellers in 2019, not least because each contain powerful stories of the dramatic circumstances surrounding how the revelations about Weinstein became public. His was no ordinary case, but involved all three journalists – and many of those quoted in their books – facing down the extraordinary personal risks involved in going public. These risks included the need to confront the menacing, and often insidious corporate power Weinstein was able to muster against them; while those subject to NDAs faced the additional perils of major financial and legal jeopardy. The books draw attention, for example, to the extent to which others can be complicit in protecting individual and corporate reputations, even in the light of compelling evidence of criminal activities. At the same time, they also suggest some of the reasons why this complicity might have occurred. Another striking feature of both books is the inclusion of many of the voices of survivors/victims. These voices provide rich, in-depth narrative accounts that help us to understand workplace sexual violence from the point of view of those at the receiving end of it. In sum, while they are not without certain limitations of their own, both books make compelling reading for management scholars. In particular, they encourage us to think about how we might begin to understand and examine – as well as likely reconsider – a range of important theoretical and empirical aspects of sexuality and power within organizations.

Before embarking on the next section we should emphasize that our focus on the Weinstein case is not a comment on its seriousness relative to other cases. Rather, it is motivated by a concern that sexual violence – especially violence committed by senior executives as senior executives – is rarely highlighted or even discussed in the management studies literature. We suggest that this absence may have played a part in enabling such activities. As a well documented and high-profile case, we believe that a consideration of Weinstein’s case represents a useful way to start to redress this problem. We are aware however, that focussing on someone who has been convicted of sexual crimes involves certain risks. In particular, it might be taken to suggest that we are implying that forms of sexual violence subject to criminal sanction are necessarily more “serious” than other forms. That is not our intent. Building on the foundational work of Kelly (1998) we see a non-hierarchical continuum of sexual aggression. For us, all acts used by men to control women – including for example, sexually based acts of intrusion, intimidation or coercion – are serious and cannot readily be distinguished from those which the criminal justice system deems to be an offence. We certainly do not wish to contribute to an environment in which, as Boyle (2019b: 25) points out, everyday, routine, intimate intrusions can drop off agendas “because of the emphasis in much scholarship (and activism) on crime”. At the same time, we are not saying that all events of sexual aggression are the same, nor that they should have the same consequences for perpetrators. Finding the right language to appropriately express our intent here remains a challenge. We prefer the inclusive term “sexual violence” (Kelly, 1998) to name Harvey Weinstein’s activities; a practice which we hope captures some of the complexities involved, without minimizing the severity (and criminality) of specific acts.

THE REALITY OF PREDATORY BUSINESSMEN

We start our discussion of the books by citing one of the many accounts of Weinstein’s survivors/victims the books include. Our example is Laura Madden’s story, who, as mentioned, was one of the first employees to agree to go on record with allegations against him. Beginning with a survivor’s/victim’s story is important in order to give primacy to the voices of those at the receiving end of Weinstein’s violence. After all, the human costs of his crimes are ultimately why the Weinstein case matters. However, Madden’s story also provides us with a springboard for developing a range of other claims about the significance of the case.

Before presenting her account, we should warn readers that her story is not what one might expect to read in a management journal. Indeed, throughout the whole canon of management and organizational scholarship, there is nothing else quite like it to our knowledge (though see Whiteman & Cooper, 2016). Nothing to compare with the shockingly vivid horror and awfulness of the picture of sexual violence it paints from the point of view of a survivor/victim. Nothing either, to approach what it implies about a particular kind of power potentially wielded by senior executives. We can start to infer from her story, for example, how other company employees did not merely turn a blind eye to Weinstein’s violence. Many must have actively facilitated it, so that sexual violence could become part of his routine; indeed, the casual way in which it seemingly occurred – redolent, for us, with a sense of (male) entitlement – implies sexual violence became something almost like a perk of his job.

Here then is Madden’s story, as told by Kantor and Twohey (2019:71/2). It follows a pattern typical of many of the others. As a young woman in her first job within the film industry, Madden found herself dispatched to Weinstein’s hotel room, excited for the chance to answer calls and run errands for the producer:

“When she arrived, champagne and sandwiches were waiting. Weinstein complimented Madden, telling her everyone on the production had noticed her talent and hard work. “He told me that I was guaranteed a permanent job in … Miramax … to start immediately,” Madden wrote in an email … “I was delighted, as this was literally my dream job.” Weinstein, wearing a bathrobe, told Madden that he was worn out from travel and wanted a massage from her. She resisted. He pushed, telling her that everyone did it, that it wasn’t a romantic request, he just needed to relax… “I felt completely caught in a situation that I intuitively felt to be wrong but wasn’t sure whether I was the problem and it was completely normal,” Madden wrote. When he took off the bathrobe and Madden placed her hands on him, she froze. He suggested that he massage her first, to put her at ease. She took her top off, as he had instructed, then her bra, and he put his hands all over her, she recounted. She felt disgusted and scared she would lose the job … It was only … after the story had broken, that Madden shared the worst details of her account. Soon her pants were off too. Weinstein stood over her, naked and masturbating. “I was lying on the bed and felt terrified and compromised and out of my depth”, she wrote. She asked him to leave her alone. But he kept making sexual requests… Weinstein suggested a shower and Madden was so numb she gave in. As the water poured around them, he continued masturbating and Madden cried so hard that the producer eventually seemed annoyed and backed off … That was when she locked herself in the bathroom, still sobbing. She thought she could still hear him masturbating on the other side of the door…“

Madden’s story, and the others like it, clearly raise many challenges and questions. Perhaps the most pressing for management scholars is the challenge it sets us to make a contribution to reducing the likelihood of others experiencing what she, and others like her, have had to endure. Even though the #MeToo movement is now making a significant difference to corporate cultures, it seems very likely that similar forms of sexual violence will continue to be committed including by the most senior executives. In this light, the following three tasks strike us as particularly important and urgent for management scholars:

- To provide a fuller conceptual understanding of those factors within corporate life which can actively facilitate sexual violence being committed by powerful individuals in organizations.

- To understand the organizational factors that enable those with power to delay trial or even evade justice when illegal acts have occurred, so that they can be ameliorated. And therefore

- To understand how to stop (the horror of) sexual violence in organizations.

Our focus on Farrow and Kantor and Twohey’s work reflects our belief that it can directly help us with these tasks. As books aimed at mass audiences however, neither frames the underpinning conceptual issues in the formal manner of academic writing. Given our more theoretical interests, we have structured the relevant issues they raise within a framework using macro-, meso- and micro-levels of analysis, and supplemented this framework with sketches of what we already know from academic research. Macro-level considerations include, for example, wider societal and cultural attitudes to sexuality generally, along with commonly held beliefs about forms of sexual expression at work. At a meso-level, our concerns center on issues such as the influence that top executives are able (and often expected) to have on corporate cultures – as well as on factors like the blind spots in standard arrangements for corporate governance, and the civil and criminal legal frameworks for dealing with sexual violence. Examples of the focus at the third, more micro-level include what Weinstein (and those who helped him) actually did in order to gain access to women who would be likely targets for his violence – as well as on how the women themselves responded in order to resist.

While this structure is useful, we should stress that Weinstein’s activities were made possible by the way in which certain elements from all three of these levels came to be aligned together. Furthermore, what we represent for convenience as relatively discrete “levels” were far from discrete in practice; they were often overlapping, interdependent and connected in complex ways. In other words, this framework is offered merely as a convenient – and provisional – heuristic to facilitate further discussion. We should also emphasize that we have made no attempt to provide comprehensive analyses. Our aim in an essay of this nature is more modest – to set out what we see as some of the key challenges and debates that the Weinstein case sets us as scholars – as groundwork for future research.

The Macro-level: “Are you sure this isn’t just young women who want to sleep with a famous movie producer to try to get ahead?”

According to Kantor & Twohey (2019:144), the question in the sub-title above was posed by Lance Maerov. Maerov, a non-executive director at Miramax whose role was to protect the interests of the company’s shareholders, asked it a few months before Weinstein’s crimes became public knowledge. Read in the light of what we now know, his words seem naïve at best. While Maerov later expressed some relief that Weinstein was finally being held to account as he felt he had mostly failed to do so over the years (Kantor & Twohey 2019:144), many will find it both shocking and outrageous that someone in his position could express such a view.

Maerov’s question nevertheless hints at some of the broader cultural attitudes to sexuality that are still widely held and taken for granted in Western societies. It also points towards the similarly unexamined assumptions about the nature of sexual behaviors often thought to be commonplace in workplaces. Both books show how these sorts of macro-level assumptions about sexual expression at work were important factors in enabling Weinstein’s sexual violence to be tolerated in the first place and then to continue for so long.

The corporate seductress

In her classic book, Men and women of the corporation, Kanter (1977:233) analyzes “role traps” for women in corporate life. She refers to these traps as the “stereotyped informal roles” commonly used to categorize women which arise because men can “respond to and understand” them. One of these traps she labels the “seductress”; a role she argues that fulfils men’s need to handle female sexuality in organizations by envisioning certain women as “overly sexual, debased seductresses”. Some might quibble with the reading of Freud that underpins the details of Kanter’s claim; we are also aware that we are taking her idea in a different direction to the one she took in the book. Nevertheless, Maerov’s question can usefully be understood as a reflection of Kanter’s fundamental insight into the way in which some women get caricatured in organizational life.

While Kanter’s work is well over 40 years old, more recent research suggests that many in contemporary organizations (women as well as men) still believe that significant numbers of women are sexually promiscuous for career advantage. For example, in an interview study of women in engineering, Fernando et al (2019:14) draw attention to participants’ beliefs about certain other female engineers, whom the participants described as displaying:

“a ‘lack of moral virtue’ [and who therefore] were subjected to sexual jokes and rumours, and seen to succeed because of their sexual wiles rather than their engineering competence. This appeared to be widely recognised, and it is notable that in all three organisations, women compared their own approaches to other women who ‘used their femininity’ to get on. Charlotte, from Luxe Autos expressed frustration that other women’s behaviour could impact on her reputation: I have a big issue with women that perhaps wear shirts that you can see through and skirts that don’t leave much to the imagination… I don’t like that and I don’t like the fact that ultimately it puts us all into a category and men think we’re all the same.”

What both Farrow and Kantor and Twohey show is that beliefs about some women’s “lack of moral virtue” influenced the way in which emerging evidence about Weinstein’s behavior was assessed. For example, according to Kantor & Twohey (2019:112-114):

“Sandeep Rehal was Weinstein’s personal assistant [who] … began to confide in … [some of the Miramax] executives about duties she found uncomfortable. Weinstein had ordered her to rent him a furnished apartment, using his corporate credit card to stock it with women’s lingerie, flowers and two bathrobes. She had to maintain a roster of women, which she referred to [as]… ‘Friends of Harvey’. Managing their comings and goings had somehow become part of her job (2019:112) … [Michelle Franklin in the London office also had] to arrange hotel room encounters for ‘Friends of Harvey’ … Like Rehal, she was charged with procuring penile injection drugs from the pharmacy, and while tidying his hotel rooms, had even picked up the discarded syringes off hotel room floors.” (2019:114)

However, although senior staff were aware of this damning evidence for years before the scandal broke, they were able to maintain a belief that “it was extramarital cheating, nothing more” (Kantor & Twohey, 2019:129). Indeed, one of Weinstein’s own favorite forms of defence was to claim that his acts of sexual violence were “consensual, extramarital dalliance[s]” (Kantor and Twohey, 2019:168). The plausibility of such beliefs and claims rely, at least in part, upon the way in which the seductress role trap is so taken for granted. The assumption that such large numbers of encounters were consensual only makes sense if we assume that many women in corporate life would jump at the chance to have sex with the man in charge.

The seductress role trap may also play a part in explaining why so many women accepted NDA payments. Kantor & Twohey (2019:53) imply that many of the women who signed NDAs felt that if their allegations became public, they would be widely assumed to have encouraged Weinstein’s behavior:

“Women signed these agreements for good reason, the attorneys had emphasized. They needed the money, craved privacy, didn’t see better opportunities, or just wanted to move on. They could avoid being branded tattle-tales, liars, flirts or habitual litigators.”

Furthermore, lawyer, Lisa Bloom, relates how there were often attempts to actively discredit survivors/victims if they refused NDAs:

“I represent many victims of wealthy and successful predators. The first thing they [the predators] do [when threatened with legal action] is go on the attack against the victim, try to dredge up anything from her life that they can find to embarrass her” (Farrow, 2019:71).

Doubtless, many of us have things in our own personal histories that would embarrass us if revealed in court. It is absurd to suggest however, that past activities represent any sort of evidence about behavior in a particular assault case. Threatening to humiliate people might work though, in as much as complainants recognize the pervasiveness of the seductress role trap in wider society. They realise that evidence of a woman having done anything remotely similar in her past will not only damage her reputation, but might well be taken to suggest complicity in the case at hand.

Sex at work is widely assumed to be “just” a trivial affair

Returning again to the question posed by Maerov with which this sub-section began, we suggest that his use of the word just – “Are you sure this isn’t just young women who want to sleep with a famous movie producer to try to get ahead?” – is telling. Maerov was already aware of many of the allegations against Weinstein when he posed the question, but in his panic to protect the company and his shareholders, he deflects to a pervasive cultural stereotype about women in the workplace. Thus, he seems to have discounted the importance of the allegations a priori. Perhaps he did so because it was “just young women” making these allegations; and/or perhaps it was because the allegations were “just” about sex. After all, Weinstein’s sexual life might conventionally seem to have nothing to do with shareholder interests.

In any event, the assumption that allegations of inappropriate sexual behaviors at work are likely to be relatively trivial, is commonly made. As Berdahl (2007:641) argues of corporate life “sexual harassment is the frequent fodder of jokes, and the idea that it is a problem worthy of attention and sanction is often dismissed”.3 It is unsurprising then that both books show how Weinstein (consciously or otherwise) was able to use these wider cultural assumptions to his advantage. Often, for example, the implication of triviality was relayed in the unnoticed minutiae of social relations within his companies. Weinstein himself, along with others, often represented his behavior as that of a “rascal” (Snead, 2013) or a “bad boy” (Kantor and Twohey, 2019:136) for instance; terms that arguably make his crimes seem child-like and inconsequential.4

Perhaps the tendency to trivialize issues connected to sexuality helps us understand one of the reasons why so many people in Weinstein’s companies knew about his activities but failed to stop him. Maybe no-one stopped him, in part, because they supposed his activities to be relatively unimportant – that he was “just” a “rascal” having sex. After all, the humor and trivialization to which sexuality is often subjected (in everyday life as much as in organizations) reflects the masculine norms that typically transmit cultural attitudes. Men with power, indeed many men, can afford to make a joke out of aspects of sexuality, not least because being subjected to the sexual advances of women is rarely threatening from most straight men’s points of view. As Berdahl (2007:650) points out, in contrast to women, straight men typically “evaluate heterosexual attention, even unwanted attention, as a neutral to positive experience”.

The Meso-level: “there was … a pimp on company payroll with only the thinnest job description to cover for his role procuring women for their boss”

Martin et al (2013:552) rightly argue that “the recent growth of CEO power, the rise of increasingly transient employment, the thickening of networks among organizations, the increase in outsourcing, and the overlap between organization leaders and governmental watchdogs all have fundamentally altered the process of rule-breaking”. As well as having many other harmful effects, the weakening of corporate controls has made it easier for executive predators to prey on vulnerable individuals – and then to go undetected. What the Weinstein affair has made only too apparent is the extent to which corporate governance focuses on executives’ formal, official powers. It has, by and large, failed to recognize the full extent of the often insidious powers they potentially wield – including over factors widely assumed to be private matters. Farrow’s comment in the sub-heading above (2019:40) emphasizes how some senior executives can, in effect, use company resources more or less as they choose; a discretion that extended, in Weinstein’s case, to an ability to use corporate lawyers and other services to both facilitate and cover up sexual violence. Indeed, the absence of (effective) monitoring of the activities of some senior people is at the heart of the issues we examine at the meso-level.

Farrow was particularly scathing about how the lack of oversight on Weinstein meant that women working in his corporations were effectively left unprotected. He documents how, for example:

“employee after employee would tell me the human resources office at the company was a sham, a place where complaints went to die (p.108) … … [or how] a large corporate conspiracy was involved in covering all this up (p. 291) [and therefore how] with painful frequency, stories of abuse by powerful people are also stories of a failure of board culture” (Farrow, 2019: 273).

Kantor and Twohey (2019:131) make a similar point about the role of non-executive director Lance Maerov. They emphasize how his:

“main concern was liability. He was trying to make sure that if anything went wrong, the company wouldn’t suffer. That was different to trying to guarantee that women would not be harassed or hurt. Once Maerov felt assured that the organization was legally protected, and with some additional financial controls in place, he decided he had done enough.”

In this section we consider those elements of Farrow’s, and Kantor and Twohey’s work which illuminate how Weinstein was able to use his senior corporate role to facilitate his crimes. We focus first on the ways in which he was able to manipulate corporate culture at both a junior as well as at board level in order to normalize sexual violence, at least to some extent. We then examine how Weinstein could use company resources to intimidate others to try to keep them quiet. Not only did he attempt to ensure the survivors’/ victims’ silence by using NDAs, he could pull many strings behind the scenes in the media to keep allegations supressed. He even made veiled threats (via agencies paid for by his company) to terrorize people – including Farrow – who might reveal evidence of his crimes. The key point about all these activities is that none is an option for ordinary, private citizens. All were enabled by his position as a senior executive; and many by the fact that his position permitted him to use large sums of company money to protect himself.

How to make a company’s culture complicit in sexual violence

Weinstein had worked in the film industry since 1979, and over a long period of time he established himself as one of its leading figures. By the mid-1990s, he was not only a highly talented Hollywood producer with a string of prestigious awards to his name; along with his brother Bob (with whom he co-owned and ran both The Weinstein Company and Miramax) he had shown himself to be a highly successful businessman. This sort of dual success had earned him a tremendous amount of influence and status within the film industry – and well beyond it – in the media generally. For many years, he was widely respected and admired. It is hardly surprising therefore that many people were predisposed to assume the best of him, even after rumors started to circulate about his predatory behavior. Indeed it seems highly unlikely that Weinstein would have been able to do the things he did – and get away with them for so long – without having first established an outstanding reputation and stature; including being genuinely good at making movies.

Nevertheless, what is one of the most puzzling (and worrying) elements of Weinstein’s case is the extent to which so many of his colleagues knew so much about his activities. To many people in the organization, his predation was a “despicable open secret” a secret that was almost “ludicrously embedded in the corporate culture” (Farrow, 2019: 40-41). Indeed, as Kantor and Twohey (2019:176) show:

“[D]ozens of Mr Weinstein’s former and current employees, from assistants to top executives, said they knew of inappropriate conduct while they worked for him. Only a handful said they ever confronted him.”

For instance, in the Catch and kill podcast episode four, a companion to the book hosted by Farrow (2020), Rowena Chiu tells of how she was hired as personal assistant to Weinstein in July 1998 in the London offices. What is particularly interesting for our purposes here is the fact that Chiu was briefed in the hiring process (albeit partially) about what she might expect as Weinstein’s assistant. Her account suggests therefore, that as early as the late 1990s, much about his behavior was already recognized within the company. Chiu explains how it was made:

“Very clear in [her] interview that Harvey was very difficult to deal with … [the interview panel] took pains to explain that I should handle him robustly. You didn’t know when he was going to lose his temper. There would be requests for massages and inappropriate talk.”

The interview had hardly prepared her however, for just how “very difficult to deal with” Weinstein would be. For example, as Chiu explains later in the podcast, Weinstein routinely walked naked around hotel rooms as he gave dictation. He explained this behavior merely by saying he was “more comfortable with less clothes”. Although she was shocked, “as assistants,” she says, “you absorb a culture that isn’t explicitly explained to you. You think, oh that’s okay, he’s far too important to wear trousers.” Like so many of the other assistants however, Chiu was subjected to sexual violence by Weinstein. She only felt able to go public with her story some 20 years later.

Weinstein influenced senior people in a rather different manner. A key to his success here appears to have been the way in which he nurtured long term relationships with colleagues, and how they consequently became increasingly dependent upon him personally as the years went by. Here is Kantor and Twohey (2019:105) describing the difficulties of getting senior people to talk about what they knew concerning Weinstein’s behavior:

“[W]hen it came to the innermost circle of executives who had served with the producer over the years … [t]alking was not in their self-interest. Why would they want the world to know that they had risen in their careers by enabling a man who seemed to be a predator?”

Speaking specifically of board members, Farrow (2019:273/4) similarly shows how:

“Over time, Weinstein was able to install loyalists [on the board] … [so that when] an adversarial board member [who had heard allegations against him]… demanded to see Weinstein’s personnel files … Weinstein was able to [enlist] … an outside attorney to render a hazy summary of its contents.”

Furthermore, it doubtless played to Weinstein’s advantage that his own brother was the only person in the company whose status came anywhere near his own. Though Bob Weinstein eventually became aware of the full extent of his brother’s criminality, he neither held him to account through formal organizational governance nor did he report him to the police. Instead, as we can see from the following extract, he wrote a personal letter to him criticizing “misbehavior” and “misdeeds”:

“I mean every time u have always minimized your behavior, or misbehavior, and always denigrated the other parties involved in some way as to deflect the fact of your own misdeeds. This always made me, sad and angry that u could or would not acknowledge your own part” (Kantor and Twohey, 2019:125).

“I want dirt on that bitch” – How corporations can instill fear and intimidation

In his discussion of whistleblowing, McAdams (1977:196) notes how, even during the 1970s, there was an inherent “danger attendant upon speaking out in the corporate sector.” If anything, Farrow’s and Kantor and Twohey’s books show that matters may perhaps have got worse since then. They demonstrate the sometimes frightening extent to which lawyers and the media could combine with his own corporation to support Weinstein’s sexual violence – mainly by intimidating survivors/victims in various ways.

One of the most prominent examples of the intertwining of the legal and corporate spheres to intimidate people is that of NDAs. NDAs were a particularly powerful weapon in Weinstein’s arsenal. As Kantor and Twohey (2019: 53-54) show:

“[T]he alternative [for survivors/victims], taking this kind of lawsuit to court, was punishing. Federal sexual harassment laws were weak … The federal statute of limitations for filing a complaint could be as short as 180 days, and federal damages were capped at $300,000 (2019:53) …[In other words] the United States had a system for muting sexual harassment claims…enabl[ing] the harassers … [rather than] stopping them” (2019:54).

Thus, Weinstein was able to get away with sexual violence for many years, in part because he essentially had free use of company lawyers to organize NDAs on his behalf. Indeed, all three journalists found many people extremely frightened to talk because they believed they were bound by NDAs. As a condition of payment being made (individual payments typically amounted to hundreds of thousands of dollars) survivors/victims were told by Weinstein’s company lawyers that they were unable to discuss their case with anyone ever again; not even with their own lawyers. Things like diaries, emails and audio recordings were all handed over so that all records of the assaults could, in effect, be erased.

Weinstein did not use lawyers simply to facilitate NDAs however. Another example of how he used them to intimidate people was provided by Farrow; this time, as the victim himself. He recounts how, on learning that Farrow had interviewed “certain people affiliated with The Weinstein Company and/or its employees and executives” (Farrow 2019: 234) as part of his investigative work, Weinstein threatened to sue him. Farrow (2019:235) received the following communication from The Weinstein Company lawyers in this context:

“All interviews that you have conducted or been involved in relating to The Weinstein Company (including its employees and executives) are the property of NBC [The National Broadcasting Company] and do not belong to you, nor are you licensed by NBC to use any such interviews.”

Weinstein also attempted to halt publication of Farrow’s article by using legal loopholes, and crucially, by using his corporate connections within the NBC – the TV network at which Farrow worked at the time – to put further pressure on Farrow. Indeed, one the most disturbing revelations in Catch and kill is the extent to which the executives at NBC itself attempted to block publication. Farrow describes a conversation in which he is told by the President of NBC News, Noah Oppenheim, that the company did not feel comfortable about pursuing Farrow’s story against Weinstein, and that he should shelve the idea. In other words, NBC were actively trying to protect Weinstein from allegations made by one of their own journalists. As Farrow (2019:405) explains:

“[I]t was a consensus about the organization’s comfort level moving forward that protected Harvey Weinstein and men like him; that yawned and gaped and enveloped law firms and PR shops and executive suites and industries; that swallowed women whole.”

Perhaps one of the reasons why Weinstein could handle NBC so effectively from his point of view was that manipulating the media is common practice in the film industry. Insider contacts are routinely used by producers to get better press for their own films, as well as to undermine other productions. For instance, according to Farrow (2019: 52) “Weinstein orchestrated an elaborate smear campaign against rival film A Beautiful Mind, planting press items claiming the protagonist, mathematician John Nash, was gay (and when that didn’t work that he was anti-semitic).” However, according to Farrow, organizations such as NBC and American Media Incorporated (AMI) – in particular the AMI publication The National Inquirer – played a key role in concealing Weinstein’s crimes. Farrow (2019:20) uses the example of when a model went to the police with a claim that Weinstein had groped her:

“Howard [Dylan Howard, editor in chief of The National Inquirer] told his staff to stop reporting on the matter – and then, later, explored buying the rights to the model’s story, in exchange for her signing a nondisclosure agreement. [Similarly] [w]hen the actress Ashley Judd claimed a studio head had sexually harassed her, almost but not quite identifying Weinstein, AMI reporters were asked to pursue negative items about her going to rehab. [And] [a]fter [actor Rose] McGowan’s claim surfaced [about Weinstein raping her] one colleague of Howard’s remembered him saying, ‘I want dirt on that bitch’.”

Furthermore, Weinstein’s former lawyer, Lisa Bloom, explained to Kantor and Twohey how working with the media went hand-in-hand with her job of defending corporate clients. In a letter to Weinstein about how to discredit Rose McGowan, Bloom advises him:

“A few well-placed articles will go a long way if things blow up down the line. We can place an article re: her becoming increasingly unglued, so that when someone googles her this is what pops up and she is discredited (2019: 101) … [Bloom also advised him on how] it is so key from a reputation management standpoint to be the first to tell the story … you should be the hero of the story not the villain. This is very doable” (Kantor and Twohey, 2019:102).

Corporations have other ways to intimidate people too. As Farrow (2019:310) says:

“For you or me, the term ‘private detective’ might conjure up images of hard-drinking ex-cops working out of rundown offices. But for moneyed corporations and individuals, the profession has long offered services that look very different.”

Such agencies can offer corporate clients services that include, for example, digging up rumors about the sexual history of people likely to make allegations of sexual misconduct against executives. They can even use James Bond-like gadgets, including “pen[s] capable of secretly recording audio” (Farrow, 2019:365/6). Indeed, according to Farrow (2019: 327)

“Lawyers working for Weinstein presented a dossier of … private investigators’ findings to prosecutors in a face-to-face meeting … employees said that those contacts were part of a ‘revolving door’ culture between the DA and high-priced investigation firms … such interactions with defense attorneys were standard procedure … for the wealthy and connected.”

An important lesson from these two books about the facilitation of sexual violence at the meso-level is that we live in a time in which weaknesses in corporate governance mean companies can actively facilitate sexual predators working at an executive level. Worse still, they can be aggressively supported by a legal system that ensures predators can be sexually violent in the workplace for decades without fear of getting stopped or for their violence to become publicly known. It took these two books, bravely written in the face of intimidation and threats, to throw light on this issue – one that had been continuing in the shadows supported by a legal-media-corporate tripartite of power and interests intent on sheltering the activities of predatory executives.

The micro-level: “He took out his penis and chased her around a desk”

As a top executive, Weinstein was able to play with the boundaries of acceptability within his organization. He was also able to start to blur the line between his fantasies and a more normative reality not only for himself, but also for others. Recall, for example, how Laura Madden felt “caught in a situation that I intuitively felt to be wrong but wasn’t sure whether I was the problem and it was completely normal”. Or how Rowena Chiu started to believe that “he’s far too important to wear trousers”. One conceptual way of thinking about what women in these situations encountered from Weinstein – and why they started to second-guess their own understanding of their experiences – is to think of it as a form of gaslighting (Stern, 2018).

Gaslighting: Using business meetings as a pretext for assault

The term was initially used as a psychoanalytical concept to understand a phenomenon in which a target individual is manipulated by another through twisting of fact and fiction – to such a degree that the target begins to doubt their own sanity and submit to the other person’s version of reality (Calef and Weinshel, 1981). Appropriately enough for a discussion of a film producer, the term originates from the title of Patrick Hamilton’s 1938 play and the famous 1944 Hollywood film in which a woman (played in the movie by Ingrid Bergman) is psychologically manipulated by her husband. More recently however, scholars have argued that gaslighting should be understood as a sociological phenomenon “rooted in social inequalities, including gender, and executed in power-laden intimate relationships” (Sweet, 2019:851). Understood in this way, gaslighting can be seen as a phenomenon that is “inter” rather than just intra-personal; one that is embedded in relations of control, exacerbating power imbalances to enable already vulnerable people to be exploited more easily.

What Weinstein seems to have been able to do in gaslighting women is to create an alternative reality which encouraged some survivors/victims into thinking his extraordinary behavior may have been how things were done in his companies. We have already seen how walking around naked could be normalized. Similarly, an agent recalls an actor they had represented recounting how Weinstein once “took out his penis and chased her around a desk during the shoot. He jumped on top of her, he pinned her down, but she got away” (Farrow, 2019:53).

He achieved this normalization by, for instance, creating spurious business meetings – meetings outwardly appearing to be ordinary business meetings with start times, agendas and intended outcomes – but which were used to ply vulnerable women with alcohol and subject them to sexual violence. As one woman testified “[h]e was a powerful boss who used the pretext of business meetings to try to pressure women into sexual interactions, and no one did anything about it” (Kantor and Twohey, 2019: 39-40). Weinstein also carried out fake “casting couch” calls to lure women in to an apartment he had asked his secretary to stock with women’s lingerie, flowers and bathrobes, so that he could direct them and “establish dominance” (Kantor and Twohey, 2019:42). Such practices were backed up by fake tales and promises that sound believable. In one case, actor Gwyneth Paltrow “learned that the producer had used her – her name, her Oscar, her success – as a means of manipulating other vulnerable women” (Kantor and Twohey, 2019:254). Weinstein had helped propel Paltrow’s career and in falsely saying she had slept with him and subsequently gone on to win an Oscar in a film he selected her for and produced “his name was synonymous with power, specifically the power to make and boost careers” (Kantor and Twohey, 2019:8).

Personal assistants’ resistance: “This is how you shut up women with allegations of abuse: you hire them back”

As we started this section of the paper with a survivor’s/victim’s account, it is appropriate to end it with a discussion of how ordinary employees (personal assistants and other office employees) tried to resist Weinstein. We should emphasize however, that the odds were very much stacked against them. Even though he had, in many cases committed criminal offences, the most obvious remedy for a victim of crime – that of reporting it to the police – was highly problematic for the women involved. Leaving aside the fact that all rape and sexual assault allegations have a comparatively low probability of success in court (Daly, and Bouhours, 2010; Jehle, 2012), much of Weinstein’s sexual violence happened without other witnesses present. The word of a junior office worker versus that of a world-famous film producer might seem unlikely to be believed. As a former employee, Lauren O’Connor, put it:

“My reward for my dedication and hard work has been to experience repeated harassment and abuse from the head of the company. I have also been witness to and heard about other verbal and physical assaults Harvey has inflicted on other employees. I am a 28 year old woman trying to make a living and a career. Harvey Weinstein is a 64 year old, world famous man and this is his company. The balance of power is me: 0, Harvey Weinstein: 10” (Kantor and Twohey, 2019:135).

No doubt part of “the balance of power” many of the women were also aware of was the media support Weinstein commanded. They would know of the likelihood that the press (as noted earlier) would find “dirt” on any “bitch” attempting to prosecute Weinstein.

Another option that might appear to have been open to survivors/victims was simply to leave Weinstein’s company; however many continued to work for him after the violence had taken place. One of the principal reasons for this seems to have been the commitment of many of the women to film industry careers. As Rowena Chiu discovered when she sought work elsewhere in the industry, the recurring question at job interviews was always: “I see you worked for Harvey for a month or so and then left … could you tell us more about this?” In fact, Chiu was forced back to Miramax because she was unable to find employment elsewhere. However, she did ultimately negotiate a position in the Hong Kong offices where she would never be alone with Weinstein (Farrow, 2020). As Knapp et al (1997:288) have shown “[t]argets [of sexual violence typically] juggle competing goals following a harassment incident, with their desire to end the harassment weighed against such objectives as avoiding reprisal by the harasser and maintaining their reputation and status in the workgroup”. However, Weinstein was able to take advantage of this kind of response. He once remarked that a Hollywood actor told him, “This is how you shut up women with allegations of abuse: you hire them back” (Farrow, 2020).

Perhaps surprisingly, NDAs were themselves also interpreted by some of the women as acts of resistance against Weinstein. This was because company lawyers often assured them that the NDA involved conditions that were binding on Weinstein too; in particular that the NDA barred Weinstein from any future unsupervised one-to-one contact with women. Discovering (often many years later) that these assurances had simply been false was often one of the main reasons motivating many to go on record against him.

In practical terms, what many of the women were left with when they remained in the workplace and realised that they were likely to be targeted, might be conceptualized, following Prasad and Prasad (2000:388), as forms of routine resistance. As opposed to formal measures (such as making a complaint to HR) routine resistance refers to “less visible and more indirect forms of opposition that can take place within the everyday worlds of organizations … [it] is often unplanned and spontaneous, occasionally being even covert in nature”. To an extent, this could be understood as an organizationally specific understanding of the heightened vigilance expected of women to keep themselves safe from sexual violence in a culture where blame is often placed on the victim (e.g. Stanko 1997). For example, in Chiu’s case, she had on one occasion deliberately worn two pairs of tights for protection (Kantor and Twohey, 2019). Another part of her routine resistance consisted of enlisting support from other junior female staff. For example, once Chiu had told fellow assistant, Zelda Perkins, about the assault she had suffered. Perkins worked the day shift and the night shift and “was always there as a ferocious guard dog” never leaving Chiu alone with Weinstein (Farrow, 2020). These informal, routine forms of resistance vividly illustrate what much research already suggests about reactions to similar events in the workplace. For example, Chamberlain et al (2008:562) show how “rather than challenging their harassment through pushing for rule enforcement, women [typically] altered their own work practices to reduce unwanted sexual contact with men”.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

In this final section, we sketch some of the implications of the issues Farrow’s and Kantor and Twohey’s work has raised for management studies, and explore what we, as management scholars, might do differently in conceptual and empirical work relevant to these concerns. Before doing so however, we briefly address the question of how commonly the same sorts of sexual violence might be carried out by other senior people in corporate life. If Weinstein’s case is that of an extreme outlier, its implications for management studies would clearly be different from a scenario in which similar sexual violence by executives is commonplace.

Evidence from other areas are relevant for moving toward a broad estimate of the likely prevalence of sexual violence committed by corporate executives. Take for example, the crisis of sexual abuse currently facing the Roman Catholic Church (and other denominations). The fact that across the globe many priests (and some nuns) have been convicted of sexual assault demonstrates that when people have access to vulnerable individuals, especially if they believe there is a low probability of exposure, a significant proportion will go on to commit sexual violence (Terry, 2015). Indeed, experience in the Catholic Church suggests that being widely thought of as a “good” person – as well as belonging to an organization in which there are strong incentives to ignore or minimize the gravity of the offences – are both factors likely to increase the amount of violence individuals commit. Documented sexual offences committed by celebrities (Gilbert, 2012), medical staff (AbuDagga et al, 2019) and university academics (Harris, 2019), all reinforce such conclusions. The scale of the problem we may face is also suggested by the significant numbers of posts by women on social media under the #MeToo and similar hashtags that involve sexual violence by bosses.

Uncomfortable though it may be, it seems clear that many corporate executives will, like Weinstein, have privileged access to vulnerable individuals. Many will also be in a position, as Weinstein was, to significantly reduce the chances of their sexual violence coming to light. In our view therefore, it seems almost inevitable that some executives (most likely a significant number in global terms) will be involved in similar kinds of sexual violence to Weinsteins’s – and will have done so with impunity – so far at least. Indeed, in recently adopting much stricter rules, especially restrictions on supervisors dating subordinates, some corporations seem already to have implicitly taken similar views. For example, in 2019, McDonald’s dismissed their CEO, Steve Easterbrook, after his relationship with a subordinate became known; even though the relationship was acknowledged to be consensual (McDonald’s, 2019).

What then can we, as organizational scholars, contribute? In many respects, whilst Catch and kill and She said, have had a powerful social and cultural influence that has gone beyond Weinstein and his individual crimes, they have not had an impact on wider structural or institutional forces – the macro and meso levels we examined. Indeed, it would be unfair to expect them to. However, what the books do is lay foundations which enable others – including management scholars – to work on these formidable challenges over the coming years. So in addition to prevalence, research in this area would need to further develop what is already known about (for example): definitions and conceptualizations of sexuality generally and of sexual violence in particular; the scope (parameters and disciplinary perspectives) of the issues at hand; epistemological issues and methods; the gaps in our current knowledge, as well as the main challenges and burning questions that still face us.

However, first and perhaps most fundamentally, we think the issues raised by the books should prompt us as a community of scholars to focus more than has historically been the case on issues relevant to sexuality in organizations. A generation ago, Hearn and Parkin (1995:4) referred to a “booming silence” on sexuality in management studies. Sadly, relatively few of us have broken this silence since. Indeed, we suspect that the colleague quoted by Jané et al (2018:415) may well be correct in their gut feeling that “it takes a bit of a higher hurdle to get into certain top tier journals when the main focus is on sex and gender” (see also Brewis, 2005). In this light, part of the ambition of our essay is to encourage change in the way the topic of sexuality in general is regarded within our discipline.

One of the more troubling aspects of the current relative silence on sexuality is that the silence extends to studies of topics on the dark side of corporate life. It might seem surprising that sexual matters are very rarely raised in debates about corporate ethics, executive wrongdoing or whistleblowing for example. Even here, the focus typically remains on the official, public (e.g. financial) roles of executives; though for an exception see Van Scotter and Roglio (2020). Among the things demonstrated by the scale of Weinstein’s use of company resources to facilitate his violence however, is that public roles cannot be neatly separated from sexuality – even if conventionally, sexuality is typically assumed to be a purely private concern (Martin, 1990).

Many of us might potentially make contributions to increasing our knowledge of sexuality as it relates to organizational life – in a range of sub-disciplines and at a variety of levels. Though our own discussions here have been animated primarily by critical, feminist and cultural theories, we would encourage future work to engage with a much wider set of ideas and disciplines. We envisage these might range from disciplines like biological sciences, through social sciences such as psychology, sociology, political science and law to the liberal arts – all disciplines with important contributions to make.

In any event, many of the directly applied conceptual issues have an urgency in needing to be considered. The potential implications of sexual violence for corporate governance and HRM policies both remain to be fully explored by management scholarship. Most corporate policies on sexual harassment, for example, typically give advice such as “if something feels off, you need to speak up” (Santos, 2020). However, these sorts of recommendations are likely to be useless, if not counterproductive, when very senior staff are involved as perpetrators. Similarly, understanding the implications for what constitutes consent when sexual relationships do occur between people at different hierarchical levels seems to be an important – and also very practical – issue to address in greater detail than has so far been attempted.

Furthermore, the issues at stake are likely to have systemic roots within wider culture, roots that could well go to the very heart of the management role as conventionally understood and practised. After all, there is likely to be a strong link between men’s violence against women and men’s (often) socially sanctioned desire to maintain power over them. We still live in a world in which most corporations are overwhelmingly dominated by men in senior positions. While it is important to stop individual sexual predators, it will probably be an endless battle – unless we start to tackle the wider structural issues more effectively. Indeed, it seems to us to be at least a possibility that sexual violence may be often be connected to other dynamics in organizations that are more widely studied. These may include, many of the “dark side” issues mentioned earlier that appear, at a surface level, to be non-sexual.

There is clearly a great deal of scope in investigating sexual violence for management scholars to make empirical contributions too. As an offshoot of the Weinstein investigation, Kantor and Twohey (2019:181) say that their editors at the New York Times:

“put together a team of reporters to look at a range of industries: Silicon Valley and the tech industry, a utopian field, supposedly unbound by the old rules, which nonetheless excluded women. Academia also seemed ripe for investigation because of the power that professors held over graduate students who wanted careers in the same field. … [The journalists also planned] to focus on low-income workers who had low visibility [and] overwhelming economic pressure … (2019: 25) [Later] … the Times sexual harrassment team expanded, digging into the stories of restaurant waitstaff, ballet dancers, domestic and factory workers, Google employees, models, prison guards and many others.”

Unfortunately, scholarly accounts of survivors’/victims’ stories concerning sexual violence in the workplace are vanishingly rare within the management and organization literature. This gap in our empirical knowledge is surely crying out to be addressed. However, conducting empirical work on perpetrators – especially those at executive level – is likely to represent a more complex challenge than work with survivors/victims, not least in terms of accessing relevant material. After all, if it does nothing else, the work of Farrow, Kantor and Twohey shows us just how ruthless and resourceful senior executives like Weinstein can be in concealing their sexual wrongdoing.

A larger problem within our discipline however, is that management researchers rarely, if ever, even consider the possibility of executives (or anyone else in organizational life) enacting sexual violence. This means that sometimes sexual violence may well have gone on under the noses of researchers – as they conducted empirical work. Indeed, one can imagine how even a long-term, in-depth ethnography of Weinstein’s company in the first decade of this century might still have entirely missed the fact that his sexual violence was well known, if the ethnographer was oblivious to any possibility that sexual offences might ever be committed by senior people in organizational life.

In part, such obliviousness may be a product of the lack of training most management researchers receive on theoretical aspects of sexuality; a factor that points us back to the importance of highlighting sexuality more generally within our discipline (i.e. conceptual issues that may not be directly related to issues of sexual violence). For example, Boyle (2019a: 29-30) argues that a large part of the reason why the infamous British TV personality, the late Jimmy Savile (see Gilbert 2012 for details of his case), was able to hide so many acts of sexual violence for so long was because:

“his ‘aberrant’ behaviour was so clearly foreshadowed in ‘typical’ male behaviour which was highly visible and, indeed, celebrated. The way he sexualised his encounters with any and every woman and girl was a clear but, crucially, ‘normal’ display of male sexual entitlement which both victims and bystanders often struggled to identify as abusive or problematic. A woman could not have behaved in the same way.”

It is conceivable that some top male executives may similarly engage in apparently “normal” displays of male sexual entitlement, the significance of which gets missed by researchers who have not been sensitized to its potentially problematic nature.

However, we see dangers in implying that the relative lack of analyses of sexuality in our discipline is an issue that can be subjected to a more or less straightforward “fix”. Indeed, we wonder whether its comparative absence in the management studies literature also demands that we take a long hard look at our own anxieties about confronting sexual violence – both as scholars and as human beings. Although the parallels may not be exact, the “booming silence” on sexuality to which Hearn and Parkin refer is open to be read as mirroring the silence of those in Weinstein’s companies who said nothing; in some ways at least. In the introduction we referred to how Weinstein’s case revealed major weaknesses in what we, as management scholars, know (and perhaps more importantly do not know) about the issues they raise. Maybe this weakness is surpassed only by what we do not want to know about sexual violence; for instance, about the possibility of our own complicity – either as bystanders or as perpetrators – across the whole continuum of sexual violence within organizational life. As one example, many of us will have heard stories about senior professors taking sexual advantage of PhD students and junior academics at research conferences. While conference organizers often have codes of conduct to try to deal with such behavior, how often is the phenomenon discussed in formal academic writing? To our knowledge, very rarely indeed.

Finally, we should make it clear that we are aware of certain limitations in the works discussed. Most obviously perhaps, both books focus almost exclusively on the Weinstein case; ideally, we would have examined more than one executive to enable comparison. It is at least a possibility, after all, that there is something about the cultural industries such as film (Hollinger 2006) or music (Larsen 2017) that make it particularly vulnerable to prestigious individuals who are sexual predators. However, perhaps unsurprisingly given the nature of the issue, there simply are no other accounts ofcontemporary executives which provide enough reliable detail for our purposes. That said, we did consider the famous memoir of former stockbroker and CEO, Jordan Belfort (2008): The wolf of Wall Street. This book contains a number of apparent admissions that Belfort committed sexual violence in his role as a CEO (for a particularly horrible example see 2008: 119-124). However, though an author’s note claims it to be “a true story based on my best recollections” we nevertheless considered the book, with its tone of locker room banter, likely to be too unreliable to base a significant part of the essay upon. Another well known contemporary case of potential relevance is that of the late Jeffrey Epstein, a convicted sex offender. He used his power as CEO of his own financial management firm, J. Epstein & Company, to procure women and under-aged girls for sexual purposes. However, we felt that his case was also problematic for detailed inclusion. Many particulars remain highly contested; not least because of the alleged involvement of very high-profile figures from political and public life (for a summary of his case see the Guardian, 2020).

Another limitation is that the Weinstein case is mostly US-centric. This is important because cultural attitudes toward sexuality – which vary widely by country (Stratford, 2013) – could prove to have been an important factor enabling Weinstein’s crimes. Perhaps in countries with generally more liberal attitudes to sexuality, his behavior might have been stopped earlier; equally however, a more liberal culture might have better enabled it to be concealed. A third limitation is that both books portray Weinstein and the survivors/victims in starkly black and white terms; the sort of criticism sometimes voiced about the #MeToo movement generally (e.g. Witt, 2020). In part, this is doubtless a product of the attitudes to Weinstein at the time the books were published, when he had already been arrested and there was a growing consensus about his guilt. However, painting a similarly morally clear cut picture might well be ill-advised for scholars conducting the kinds of work commended above. Such research is likely to be conducted in an environment where often, establishing rights and wrongs will prove difficult, and researchers will be confronted by many ambiguities and ambivalences – as much in the data they elicit – as in their own personal views and loyalties.

Overall however, we think that the wider implications of the Weinstein case are highly complex at both a conceptual and empirical level. They also pose a number of practical challenges of great importance to society. For both these reasons we suggest that understanding and tackling sexual violence in organizations should represent another of the “societal grand challenges” (George, et al, 2016) that face management scholars today.

NOTES

1. The phrase ‘me too’ was coined in 2006 by social activist, Tarana Burke, to support women and girls of color who were victims of sexual violence (Fernando and Prasad, 2019). It became a hashtag with the rise of social media; when revelations about Harvey Weinstein were made public in October 2017, its worldwide prominence grew exponentially. For a detailed scholarly account of the #MeToo phenomenon, see Boyle (2019a).

[1] Our focus is on women subject to sexual violence by more powerful men, the most frequently reported form of workplace sexual violence. It is important to acknowledge from the outset however that LGBTQIA+ people face similar threats in the workplace; people of any gender suffer sexual violence from peers; and, although it is the least commonly reported form, women are sexually violent to more junior men in workplace settings (Berdahl, 2007).

2. Our focus is on women subject to sexual violence by more powerful men, the most frequently reported form of workplace sexual violence. It is important to acknowledge from the outset however that LGBTQIA+ people face similar threats in the workplace; people of any gender suffer sexual violence from peers; and, although it is the least commonly reported form, women are sexually violent to more junior men in workplace settings (Berdahl, 2007).